70 Pro Death Penalty Quotes by Judges from the U.S.A

|

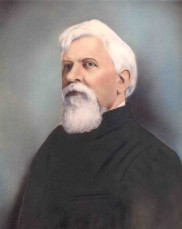

"I have ever had the single aim of justice in view... 'Do equal

and exact justice,' is my motto, and I have often said to the grand jury,

'Permit no innocent man to be punished, but let no guilty man escape.'" Letter

to U.S. Attorney General Augustus Hill Garland (May 27, 1885). “The object of punishment is to... lift the man up; to stamp out his

bad nature and wicked disposition.” |

|

But you will not be there. The rivulet will run its soaring course to the sea. The timid desert flowers will put forth their tender shoots. The glorious valleys in this imperial domain will blossom as the rose. Still you will not be there. From every treetop, some wildwood songster will carol his mating song. Butterflies will sport in the sunshine. The gentle breeze will tease the tassels of the wild grasses and all nature will be glad. But you will not be there to enjoy it. Because I command the sheriff of the county to lead you away to some remote spot, swing you by the neck from a knotting bough of some sturdy oak and let you hang until dead. |

|

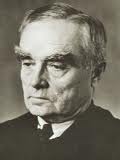

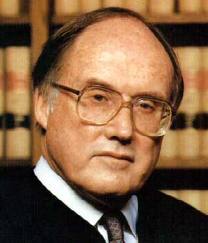

“We are concerned here only with the imposition of capital punishment for the crime of murder, and when a life has been taken deliberately by the offender, we cannot say that the punishment is invariably disproportionate to the crime. It is an extreme sanction suitable to the most extreme of crimes.”

Majority opinion in 7-2 ruling that the death penalty is a constitutionally acceptable form of punishment for premeditated murder (July 2, 1976) Held in the Supreme Court in

Gregg v. Georgia. – “We may nevertheless assume

safely there are murders, such as those who act in passion, for whom the threat

of death has little or no deterrent effect. But for many others, the death

penalty undoubtedly, is a significant deterrent. There are carefully

contemplated murders, such as murder for hire, where the possible penalty of

death may well enter the cold calculus that precedes the decision to act.”

Justice Stewart held in the Supreme Court in Gregg v. Georgia: - “Although some of the studies suggest that the death penalty may not function as a significantly greater deterrent than lesser penalties, there is no convincing empirical evidence supporting or refuting this view.” |

|

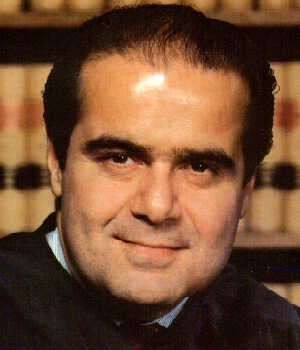

"Justice Blackmun begins his statement [declaring Blackmun's opposition to capital punishment] by describing with poignancy the death of a convicted murderer by lethal injection. He chooses, as the case in which to make that statement, one of the less brutal of the murders that regularly come before us, the murder of a man ripped by a bullet suddenly and unexpectedly, with no opportunity to prepare himself and his affairs, and left to bleed to death on the floor of a tavern. The death-by-injection which Justice Blackmun describes looks pretty desirable next to that. It looks even better next to some of the other cases currently before us, which Justice Blackmun did not select as the vehicle for his announcement that the death penalty is always unconstitutional, for example, the case of the 11-year-old girl raped by four men and then killed by stuffing her panties down her throat. See McCollum v. North Carolina. How enviable a quiet death by lethal injection compared with that!" Callins v. Collins 510 U.S. 1141 (1994) (Scalia, J., concurring in denial of cert). "The Court thus proclaims itself sole arbiter of our Nation's moral standards—and in the course of discharging that awesome responsibility purports to take guidance from the views of foreign courts and legislatures. Because I do not believe that the meaning of our Eighth Amendment, any more than the meaning of other provisions of our Constitution, should be determined by the subjective views of five Members of this Court and like-minded foreigners, I dissent. Words have no meaning if the views of less than 50 percent of death penalty States can constitute a national consensus. Our previous cases have required overwhelming opposition to a challenged practice, generally over a long period of time.” With the death penalty,

on the other hand, I am part of the criminal law machinery that imposes death,

which extends from the indictment to the jury conviction to rejection of the

last appeal. I am aware of the ethical principle that one can give material

cooperation to the immoral act of another when the evil that would attend

failure to cooperate is even greater: for example, helping a burglar to tie up

a householder where the alternative is that the burglar will kill the

householder. [God's Justice and Ours By: Antonin Scalia, Supreme Court Justice 18 November 2002] Scalia Questions Catholic Opposition to Death Penalty (Fox News | Tuesday, February 05, 2002 | AP) – Scalia, who has consistently upheld capital cases, told Georgetown students that the church has a much longer history of endorsing capital punishment. "No authority that I know of denies the 2,000-year-old tradition of the church approving capital punishment," he said. "I don't see why there's been a change." Scalia Questions Catholic Opposition to Death Penalty (Fox News | Tuesday, February 05, 2002 | AP) - In Chicago on Jan. 25, Scalia said, "In my view, the choice for the judge who believes the death penalty to be immoral is resignation rather than simply ignoring duly enacted constitutional laws and sabotaging the death penalty." His remarks were transcribed by the event sponsor, the Pew Forum. It is a

matter of great consequence to me, therefore, whether the death penalty is

morally acceptable, and I want to say a few words about why I believe it is.

Being a Roman Catholic and being unable to jump out of my skin, I cannot

discuss that issue without reference to Christian tradition and the church’s

magisterium discussed earlier in this conference by Cardinal Dulles. Those of

you to whom this makes no difference must bear with those portions of my

remarks. [God's Justice and Ours By: Antonin Scalia, Supreme Court Justice 18 November 2002] The death

penalty is undoubtedly wrong unless one accords to the state a scope of moral

action that goes beyond what is permitted to the individual. [God's Justice and Ours By: Antonin

Scalia, Supreme Court Justice 18 November 2002] In my view,

the major impetus behind modern aversion to the death penalty is the equation

of private morality with governmental morality. That is a predictable, though I

believe erroneous and regrettable, reaction to modern democratic

self-government. [God's Justice and Ours By: Antonin Scalia, Supreme Court Justice 18 November 2002] Few doubted the morality of the death penalty in the age that believed

in the divine right of kings, or even in earlier times, St. Paul had this to

say : ... "Let every soul be subject unto the higher powers, for there is

no power but of God. The powers that be are ordained of God. Whosoever,

therefore, resisteth the power resisteth the ordinance of God, and they that

resist shall receive to themselves damnation, for rulers are not a terror to

good works, but to the evil. Wilt thou then not be afraid of the power? Do that

which is good and thou shalt have praise of the same. For he is the minister of

God to thee for good. But if thou do that which is evil, be afraid, for he

beareth not the sword in vain, for he is the minister of God, a revenger to execute

wrath upon him that doth evil. Wherefore, ye must needs be subject not only for

wrath, but also for conscience sake." Rom 13:1-5. [God's Justice and Ours By: Antonin Scalia, Supreme Court Justice 18

November

This is not

the Old Testament, I emphasize, but St. Paul. One can understand his words as

referring only to lawfully constituted authority or even only to lawfully

constituted authority that rules justly, but the core of his message is that

government, however you want to limit that concept, derives its moral authority

from God. It is the minister of God with powers to revenge, to execute wrath,

including even wrath by the sword, which is unmistakably a reference to the

death penalty. [God's Justice and Ours By: Antonin Scalia, Supreme Court Justice 18 November 2002] Paul, of

course, did not believe that the individual possessed any such powers. Indeed,

only a few lines before the passage I just read, he said, "Dearly beloved,

avenge not yourselves, but rather give place unto wrath, for it is written

vengeance is mine, saith the Lord." And in this world, in Paul’s world,

the Lord repaid, did justice through his minister, the state. [God's Justice and Ours By: Antonin

Scalia, Supreme Court Justice 18 November 2002] These

passages from Romans represent, I think, the consensus of Western thought until

quite recent times – not just of Christian or religious thought, but of secular

thought regarding the powers of the state. That consensus has been upset, as I

suggested, by the emergence of democracy. [God's Justice and Ours By: Antonin

Scalia, Supreme Court Justice 18 November 2002] [I]t seems to me that the more Christian a country is the less likely it is to regard the death penalty as immoral. Abolition has taken its firmest hold in post–Christian Europe, and has least support in the church–going United States. I attribute that to the fact that, for the believing Christian, death is no big deal. Intentionally killing an innocent person is a big deal: it is a grave sin, which causes one to lose his soul. But losing this life, in exchange for the next? The Christian attitude is reflected in the words Robert Bolt’s play has Thomas More saying to the headsman: 'Friend, be not afraid of your office. You send me to God' And when Cramner asks whether he is sure of that, More replies, "He will not refuse one who is so blithe to go to him." . . . For the nonbeliever, on the other hand, to deprive a man of his life is to end his existence. God’s Justice and Ours, 123 First Things 17.

For the

non-believer, on the other hand, to deprive a man of his life is to end his

existence – what a horrible act. And besides being less likely to regard death

as an utterly cataclysmic punishment, the Christian is also more likely to

regard punishment in general as deserved. The doctrine of free will, the

ability of man to resist temptations to evil is central to the Christian

doctrine of salvation and damnation, heaven and hell. The post-Freudian

secularist, on the other hand, is more inclined to think that people are what

their history and circumstances have made them, and there is little sense in

assigning blame. [God's

Justice and Ours By: Antonin Scalia, Supreme Court Justice 18 November

2002] There have

been Christian opponents of the death penalty just as there have been Christian

pacifists, but neither of those positions has even been predominant in the church.

Its current predominance is the handiwork of Napoleon, Hegel and Freud rather than

of St. Thomas and St. Augustine. [God's

Justice and Ours By: Antonin Scalia, Supreme Court Justice 18 November 2002] It seems to

me that the reaction of people of faith to this tendency of democracy to

obscure the divine authority behind government should be not resignation to it

but resolution to combat it as effectively as possible, and a principal way of

combating it, in my view, is constant public reminder that – in the words of

one of the Supreme Court’s religion cases in the days when we understood the

religion clauses better than I think we now do – "we are a religious

people whose institutions presuppose a supreme being. In the seminar Scalia were asked about innocent persons who can been executed. He answered: "I think the question, if I got it correctly, was do I think the death penalty is immoral because it will – I have to say it – it will inevitably lead at some point to the condemnation of someone who is innocent. Well, of course it will. I mean, you cannot have any system of human justice that is going to be perfect. And if the death penalty is immoral for that reason, so is life in prison. You think you’re not going to have innocent people put in prison for life? It’s one of the risks of living in an organized human society. And it’s one that we all say, it’s better than the alternative, which is to be subjected to constant crime. I don’t think that the system becomes immoral because it cannot be perfect.” “Now, we make enormous efforts, in this country more than any others, to make sure that the death penalty is not inflicted arbitrarily or wrongfully. You heard earlier that it’s something like 10 years between the time of the conviction and the ultimate execution of the sentence, during which lawyers and death abolition advocates are scouring the country to find out why this person should not be killed. That’s the best we can do in any human system, so I don’t think you can judge the validity of any criminal law system on the basis of whether now and then it might make a mistake." “A single case—not one—in which it is clear that a person was executed for a crime he did not commit. If such an event had occurred in recent years, we would not have to hunt for it; the innocent’s name would be shouted from the rooftops.” "[I] believe that our people’s traditional belief in the right of trial by jury is in perilous decline. That decline is bound to be confirmed, and indeed accelerated, by the repeated spectacle of a man’s going to his death because a judge found that an aggravating factor existed. We cannot preserve our veneration for the protection of the jury in criminal cases if we render ourselves callous to the need for that protection by regularly imposing the death penalty without it." Ring v. Arizona) (concurring). "Today's decision is the pinnacle of our Eighth Amendment death-is-different jurisprudence. Not only does it, like all of that jurisprudence, find no support in the text or history of the Eighth Amendment; it does not even have support in current social attitudes regarding the conditions that render an otherwise just death penalty inappropriate. Seldom has an opinion of this Court rested so obviously upon nothing but the personal views of its members." Atkins v. Virginia (dissenting). Where Scalia is caught in an obvious contradiction is in his endorsement of the notion that only those prepared to vote for the death penalty should be allowed on a jury, and that appeals court judges opposed to the death penalty should recuse themselves in capital cases. "There is something to be said," Scalia writes in his dissent in Atkins, "for popular abolition for the death penalty; there is nothing to be said for its incremental abolition by this court." [Atkins v. Va., supra note 28, 536 U.S., at 353 (Scalia, J., dissenting)] The American people have determined that the good to be derived from capital punishment in deterrence and perhaps most of all in the meting out of condign justice for horrible crimes — outweighs the risk of error. It is no proper part of the business of this court, or of its justices, to second-guess that judgment, much less to impugn it before the world. “You want to have a fair death penalty? You kill; you die. That’s fair. You wouldn’t have any of these problems about, you know, you kill a white person, you kill a black person. You want to make it fair? You kill; you die.” On executing minors: "What a mockery today's opinion makes of Hamilton's expectation, announcing the Court's conclusion - that the meaning of our Constitution has changed over the past 15 years—not, mind you, not that this Court's decision 15 years ago was wrong, but that the Constitution has changed. The Court reaches this implausible result by purporting to advert, not to the original meaning of the Eighth Amendment, but to "the evolving standards of decency," of our national society. It then finds, on the flimsiest of grounds, that a national consensus which could not be perceived in our people's laws barely 15 years ago now solidly exists." Roper v. Simmons (dissenting). On the point of the Court's Roper decision: "I watched one television commentary on the case in which the host had one person defending the opinion on the ground that people should not be subjected to capital punishment for crimes they commit when they are younger than eighteen, and the other person attacked the opinion on the ground that a jury should be able to decide that a person, despite the fact he was under eighteen, given the crime, given the person involved, should be subjected to capital punishment. And it struck me how irrelevant it was, how much the point had been missed. The question wasn’t whether the call was right or wrong. The important question was who [i.e., the Courts or Congress] should make the call." Speech at Woodrow Wilson Center, 2005. The case of Kansas v. Michael Lee Marsh, wrote: "...Reversal of an erroneous

conviction on appeal or on habeas, or the pardoning of an innocent condemnee

through executive clemency, demonstrates not the failure of the system but its

success. Those devices are part and parcel of the multiple assurances that are

applied before a death sentence is carried out... As a consequence of the sensitivity of

the criminal justice system to the due-process rights of defendants sentenced

to death, almost two-thirds of all death sentences are overturned.... June 26, 2006 The truth, as Justice Scalia showed in his scalding concurrence in Kansas v. Marsh, is that no neutral source has endorsed the notion that, in the modern (post-Gregg) era, a single factually innocent person has been executed in this country: It should be noted at the outset that the dissent does not discuss a single case--not one--in which it is clear that a person was executed for a crime he did not commit. If such an event had occurred in recent years, we would not have to hunt for it; the innocent's name would be shouted from the rooftops by the abolition lobby. The dissent makes much of the new-found capacity of DNA testing to establish innocence. But in every case of an executed defendant of which I am aware, that technology has confirmed guilt. “Does [the death penalty] constitute cruel and unusual punishment?” Scalia asked. “The answer is no. It does not, even if you don’t allow mitigating evidence in. I mean, my Court made up that requirement.... I don’t think my Court is authorized to say, oh, it would be a good idea to have every jury be able to consider mitigating evidence and grant mercy. And, oh, it would be a good idea not to have mandatory death penalties...” At the end of his career on the bench, former Justice John Paul Stevens' view of the death penalty had evolved. Although he voted to reinstate it in 1976, by 2008, he wrote that the death penalty represents "the pointless and needless extinction of life with only marginal contributions to any discernible social or public purposes." For the first time, in a concurrence in a case dealing with lethal injection, Stevens opined that the death penalty was unconstitutional. Justice Antonin Scalia, joined by Justice Clarence Thomas, wrote separately to address Stevens' concern. "The conclusion is insupportable as an interpretation of the Constitution," Scalia wrote, "which generally leaves it to democratically elected legislatures rather than courts to decide what makes significant contribution to social or public purposes." Scalia argued that the text of the Constitution recognizes the death penalty as a "permissible legislative choice." "The Fifth Amendment expressly requires a presentment or indictment of a grand jury to hold a person to answer for a 'capital, or otherwise infamous crime,'" Scalia wrote, "and prohibits deprivation of 'life' without due process of law." Scalia criticized Stevens for "barely" acknowledging a "significant body of recent evidence that capital punishment may well have a deterrent effect, possibly a quite powerful one." And, as a final blow, he wrote, "I take no position on the desirability of the death penalty, except to say that its value is eminently debatable and the subject of deeply, indeed passionately, held views-which means, to me, that it is pre-eminently not a matter to be resolved here. And especially not when it is explicitly permitted by the Constitution." “This is an execution, not surgery. . . . Where does that come from, that you must find the method of execution that causes the least pain? We have approved electrocution. We have approved death by firing squad. I expect both of those have more possibilities of painful death than the protocol here.” During the speech, Scalia noted the presence of the protests, and said that he found no contradiction between his Catholic faith and his support of the death penalty. He added, "If I thought that Catholic doctrine held the death penalty to be immoral, I would resign," he said. "I could not be a part of a system that imposes it." [Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia delivered the keynote address as part of the centennial celebration of the Duquesne University Law School on Sunday 25 September 2011] |

|

"Indeed, the decision that capital punishment may be the appropriate sanction in extreme cases is an expression of the community's belief that certain crimes are themselves so grievous an affront to humanity that the only adequate response may be the penalty of death."

|

|

|

|

Our dangers do not lie in too little tenderness to the accused. Our procedure has been always haunted by the ghost of the innocent man convicted. It is an unreal dream. What we need to fear is the archaic formalism and the watery sentiment that obstructs, delays, and defeats the prosecution of crime. |

|

“We keep our hands out of a flame because it hurt the very first time (not the second, fifth or 10th time) we touched the fire and it is from this it can be contemplated why I strongly adhere to the doctrine that a criminal who has brutally taken somebody’s life has no natural right to his own life and should be paying with his own life, it is because the value of a life can only be explained by the people who were dependent on that life, and as for thinkers who think that punishment should be more reformative then I contend that capital punishment is reformative, we are reforming, not the hanged individual.” |

|

1992 - During another interview, Sabo called himself a "tough judge," but emphasized that he also is fair and impartial and has always followed the law. "I didn't commit the crime," he said. "I was only the mechanic through which the jury verdict was carried out." |

|

The capital punishment opinion came in 1994, when Judge Beezer, writing for the majority in a 6-to-5 decision, said that hanging was an acceptable form of execution. The ruling was in the case of Charles Rodman Campbell, a death row inmate who had been convicted of killing two women and a girl and who objected to the method of execution to which he had been sentenced: by hanging. He contended that hanging amounted to cruel and unusual punishment. Washington State offered lethal injection as an alternative form of execution, but only if the condemned person requested it. Mr. Campbell said his religious convictions would not permit him to choose between methods. Judge Beezer ruled that when it hanged people, the state exercised proper safeguards against slow death by strangling and other possibilities of unnecessary cruelty. “Campbell is not entitled to a painless execution, but only to one free of purposeful cruelty,” the judge wrote. |

|

Just as the legislature legitimately may conclude that capital punishment deters crime, so it may conclude that capital punishment serves a vital social function as society’s expression of moral outrage. (Robert Bork, brief for the United States in Gregg v. Georgia before the U.S Supreme Court) Look at the Pope’s words in Evangelium Vitae: The state “ought not go to the extreme of executing the offender except in cases of absolute necessity: in other words, when it would not be possible otherwise to defend society. Today, however, as a result of steady improvements in the organization of the penal system, such cases are rare, if not practically nonexistent.” (Emphases deleted and added.) Two things are to be noted. First, imprisonment does not exact just retribution for particularly horrible crimes. Death penalty cases involve crimes of almost unbelievable savagery and brutality. [Robert Bork on Scalia & Capital Punishment Oct 2002] Life imprisonment does not, in any event, fully protect society. Imprisoned murderers have killed guards and other prisoners. They have been paroled or escaped and killed again. Just two years ago, seven hardened criminals, one of whom was serving eighteen life sentences, escaped from a maximum-security Texas prison. A few weeks later, while robbing a sporting goods store, they killed a police officer, shooting him thirteen times and then driving over his body. The blood of the murderers’ new victims is at least partially on the hands of those who make the execution of such killers impossible. [Robert Bork on Scalia & Capital Punishment Oct 2002] |

|

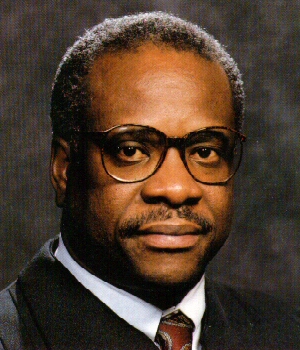

SENATOR THURMOND: Would you give the

committee your views on the validity of placing some reasonable limitations on

the number of post-trial appeals in death penalty cases? JUDGE THOMAS: The death penalty is the harshest penalty that can be imposed, and it is certainly one that is unchangeable. And we should be most concerned about providing all the rights and all the due process that can be provided and should be provided to individuals who may face that kind of a consequence. I would be concerned, of course, that we would move too fast, that if we eliminate some of the protections that perhaps we may deprive that individual of his life without due process. I believe that there should be reasonable restrictions at some point, but not to the point that an individual is deprived of his constitutional protections. |

|

Lectures, II, ii. Of the executive department - With regard, says Rousseau, to the prerogative of granting pardon to criminals, condemned by the laws of their country, and sentenced by the judges, it belongs only to that power, which is superior both to the judges and the laws ― the sovereign authority. |

|

Many capital punishment advocates believe, furthermore, that the possibility of executing the innocent does not justify the abolition of the death penalty. Even if a few innocent lives are taken, they argue, the deterrent effects of the death penalty are worth it. As Detroit lawyer Stephen Markman puts it, “the death penalty serves to protect a vastly greater number of innocent lives than are likely to be lost through its erroneous application . . . a society would be guilty of a suicidal failure of nerve if it were to forgo the use of an appropriate and deserved punishment simply because it is not humanly possible to eliminate the risk of mistake entirely.” Public opinion reflects Markman’s contention: A

June 1995 Gallup poll showed that 57 percent of Americans would still favor the

death penalty even if one out of one hundred of those executed were undeniably

innocent. |

|

"That the ever present potentiality in California of the death penalty, for murder in the commission of armed robbery, each year saves the lives of scores, if not hundreds of victims of such crimes, I cannot think, reasonably be doubted by any judge who has had substantial experience at the trial court level with the handling of such persons. I know that during my own trial court experience...included some four to five years (1930-1934) in a department of the superior court exclusively engaged in handling felony cases, I repeatedly heard from the lips of robbers...substantially the same story: 'I used a toy gun [or a simulated gun or a gun in which the firing pin or hammer had been extracted or damaged] because I didn't want my neck stretched.' (The penalty, at the time referred to, was hanging.)"

|

|

|

The power of impeachment is given by this Constitution, to bring great offenders to punishment. It is calculated to bring them to punishment for crimes which it is not easy to describe, but which everyone must be convinced is a high crime and misdemeanour against the government. [July 28, 1788, p. 107. North Carolina's Debates, in Convention, on the adoption of the Federal Constitution (1787) Reported in The Debates, Resolutions, and other Proceedings, in Convention, on the adoption of the Federal Constitution, as recommended by the General Convention at Philadelphia, on the 17th of September, 1787 (1830), edited by Jonathan Elliot.]

If they

were punishable for exercising their own judgment, and not that of their

constituents, no man who regarded his reputation would accept the office either

of a Senator or President. Whatever mistake a man may make, he ought not to be

punished for it, nor his posterity rendered infamous. But if a man be a

villain, and wilfully abuses his trust, he is to be held up as a public

offender, and ignominiously punished. |

|

27 June 1991 - Justice though due to the accused, is due to the accuser also. The concept of fairness must not be strained until it is narrowed to a fillment. We are to keep the balance true. |

|

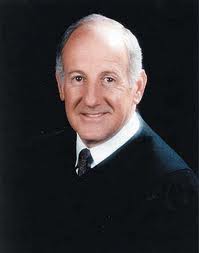

Many interests are

affected by this. The public, including the families and friends of victims and

of those convicted, has a keen interest in finality and enforcement of the law.

Unnecessary delay in death penalty cases frustrates the prosecution and the defense,

as well as those people and institutions awaiting guidance from the high

court's decisions in civil and noncapital criminal cases. Moreover, when a

reversal occurs long after judgment, and a retrial is necessary, memories may

have faded and witnesses often are unavailable. [Reform death penalty appeals:

Allowing state appellate courts to review cases would help ease a huge backlog.

By Ronald M. George January 7, 2008] |

|

The privilege of opening the first trial in history for crimes against the peace of the world imposes a grave responsibility. The wrongs which we seek to condemn and punish have been so calculated, so malignant, and so devastating, that civilization cannot tolerate their being ignored, because it cannot survive their being repeated. That four great nations, flushed with victory and stung with injury stay the hand of vengeance and voluntarily submit their captive enemies to the judgment of the law is one of the most significant tributes that Power has ever paid to Reason. [Opening Address to the International Military Tribunal at the Nuremberg Trials (November 10, 1945).] If we can cultivate in the world the idea that aggressive war-making is the way to the prisoner's dock rather than the way to honors, we will have accomplished something toward making the peace more secure. [Opening Address to the International Military Tribunal at the Nuremberg Trials (November 10, 1945).] When we went to school we were told that we were governed by laws, not

men. As a result of that, many people think there is no need to pay any

attention to judicial candidates because judges merely apply the law by some

mathematical formula and a good judge and a bad judge all apply the same kind

of law. The fact is that the most important part of a judge's work is the

exercise of judgment and that the law in a court is never better than the

common sense judgment of the judge that is presiding. [Reported in Eugene

Gerhart, America's Advocate: Robert H. Jackson (1958), p. 289.] The qualities of a good prosecutor are as elusive and as impossible to define as those which mark a gentleman. And those who need to be told would not understand it anyway. A sensitiveness to fair play and sportsmanship is perhaps the best protection against the abuse of power, and the citizen's safety lies in the prosecutor who tempers zeal with human kindness, who seeks truth and not victims, who serves the law and not factional purposes, and who approaches his task with humility. ["The Federal Prosecutor", 24 J. Am. Judicature Soc'y 18 (1940) (Address delivered at the Second Annual Conference of United States Attorneys, April 1, 1940).] |

|

The plurality opinion in Trop v. Dulles, supra, is of special interest, since it is this opinion, in large measure, that provides the foundation for the present attack on the death penalty. It is anomalous that the standard urged by petitioners -- "evolving standards of decency that mark the progress of a maturing society" (356 U.S. at 101) -- should be derived from an opinion that so unqualifiedly rejects their arguments. Chief Justice Warren, joined by Justices Black, DOUGLAS, and Whittaker, stated flatly:

At the outset, let us put to one side the death penalty as an index of the constitutional limit on punishment. Whatever the arguments may be against capital punishment, both on moral grounds and in terms of accomplishing the purposes of punishment -- and they are forceful -- the death penalty has been employed throughout our history, and, in a day when it is still widely accepted, it cannot be said to violate the constitutional concept of cruelty. Id. at 99. The issue in Trop was whether forfeiture of citizenship was a cruel and unusual punishment when imposed on a wartime deserter who had gone "over the hill" for less than a day and had willingly surrendered. In examining the consequences of the relatively novel punishment of denationalization, Chief Justice Warren drew a line between "traditional" and "unusual" penalties:

While the

State has the power to punish, the [Eighth] Amendment stands to assure that

this power be exercised within the limits of civilized standards. Fines,

imprisonment and even execution may be imposed depending upon the enormity of

the crime, but any technique outside the bounds of these traditional penalties

is constitutionally suspect. |

|

The Virginia Supreme Court on Friday 13 January 2011 denied the death penalty appeal of a serial killer for the slayings of two George Washington University students in 1988. The unanimous decision clears the way for Alfredo R. Prieto to be executed in Virginia for the deaths of college sweethearts Rachael Raver and Warren Fulton III. Prieto appealed his conviction and his two death sentences based on dozens of claims of trial and sentencing errors concerning evidence, testimony and jury instructions. Justices said they found no reason to overturn the conviction or return the case to Circuit Court. "Furthermore," Justice Leroy F. Millette Jr. wrote, "we find no reason to commute or set aside the sentences of death." |

|

The high court unanimously upheld the death sentence Thursday 16 August 2012. The justices ruled that the penalty is proportionate to the crime and justified by aggravating circumstances – that Robert killed a prison guard and the murder occurred during an escape attempt.

"This was not merely an escape attempt on the spur of the moment where events spiraled out of control. Here the record reflects that Robert had been planning his escape attempt, which included the murder of a corrections officer, for well over a month. His planning stage included obtaining the lead pipe eventually used to kill Johnson," Chief Justice David Gilbertson wrote.

The circuit judge was not influenced by passion or prejudice in sentencing Robert to death, but instead considered that Robert is dangerous because he has threatened to kill again, has a violent history, is unlikely to be rehabilitated and committed a severe crime, the Supreme Court said. The justices said their review of the sentence was particularly important because Robert has demanded to be executed.

"Robert's persistent efforts to hasten his own death necessitate

intense scrutiny to guarantee his desire to die was not a consideration in the

sentencing determination. We do not participate in a program of state-assisted

suicide," Gilbertson wrote. |

|

“If cowardly and dishonorable men sometimes shoot unarmed men with army pistols or guns, the evil must be prevented by the penitentiary and gallows, and not by a general deprivation of a constitutional privilege.” [Honorable J. A. Williams was a circuit Judge in Arkansas in 1878. Arkansas Supreme Court, 1878] |

|

Judge Edward Cowart said, when

sentencing Ted Bundy to death: "It is ordered that you be put

to death by a current of electricity, that current be passed through your body

until you are dead. Take care of yourself, young man. I say that to you

sincerely; take care of yourself. It's a tragedy for this court to see such a

total waste of humanity as I've experienced in this courtroom. You're a bright

young man. You'd have made a good lawyer, and I'd have loved to have you

practice in front of me, but you went the wrong way, partner. Take care of

yourself. I don't have any animosity to you. I want you to know that. Take care

of yourself." |

|

If judges would make their decisions just, they should behold neither plaintiff, defendant, nor pleader, but only the cause itself.

|

|

The Supreme Court Ruled that capital punishment for minors violates the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment, the court reversed its 1980 decision that allowed executions of convicts who were 16 or 17 at the time of their crimes. In her dissent Justice O’Connor wrote: “I would demand a clearer showing that our society truly has set its face against this practice before reading the Eighth Amendment as categorically to forbid it.” |

|

"The scales of life and death tilt unquestionably to the side of death," Merritt said. "You not only forfeited your right to live among us, but you've forfeited your right to live at all." [On sentencing John Kalisz to death on Tuesday 6 March 2012] |